"I used to sing at nightclubs to survive, those years in the 80s" - Sox

Daniel Phakoe, better known as ‘Sox’, passed away on April 28 2022 after a long illness. Sox started his music career as a drummer for a group called Joyco from Maokeng in Kroonstad, where he grew up. He later performed with the Hot Soul Singers and Public Affairs. As a solo artist he is best known for his 1988 hit ‘Don’t Call me Le Ja Pere’ ('Don’t Call me a Horse Eater'), a plea to avoid racial stereotypes. The following is a transcription of an interview with him at his home in Thembisa, east of Johannesburg, on 15 November 2009. It has been edited for clarity.

(When did you get into music?)

Recording professionally, it was 1987. With a group called Public Affairs. Our first album was Master, with Eric Frisch (Productions). That was me, people thought it was CJB, the voice. Because I used to sing at nightclubs to survive, those years in the 80s. I used to play in the nightclubs a lot, in Johannesburg. You know, the nightclubs in town then, there was a time when they would book you for about two months or three months. I was doing cover versions — I didn’t have my own songs by then — international stuff. Remember, in the 80s, every Christmas time, there was this thing of waiting to hear the latest album from Lionel Richie, Kool & the Gang. People they didn’t buy local music then, until Brenda [Fassie] comes along in 1983. Then Brenda changed the whole complexion of this music industry. It was ‘Weekend Special’, which people thought it was Diana Ross! Only to discover that it was a local girl.

And then all these musicians who were hiding, didn’t even want to compose their own songs, then after Brenda, 'Weekend Special', then CJB comes along, Phumi Maduna – Cheek To Cheek came after Brenda was going to have a baby in Cape Town - Bongani, her first-born. Then Brenda came back and did the full album of Weekend Special. Those LPs were called maxi singles back then. it was only two tracks. It was ‘Weekend Special’ first. It wasn’t an LP, and on it was written ‘not for sale’. There were record companies who were selling them (but it was meant to be) for radio stations and record bars to make people aware so-and-so is coming with a new album.

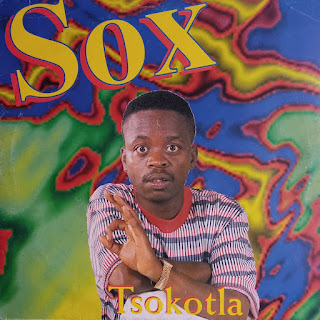

|

| Tsokotla (1995) |

(What does the label ‘bubblegum’ mean to you?)

Bubblegum, it was irritating at first. But if Brenda didn’t mind, who are we to mind? Because she’s the one who started the whole thing. She didn’t (mind).

These kwaito guys, they didn’t want to call us bubblegum musicians, they wanted to call it ‘oldskool’ musicians. (journalists, DJs..). there are some, from Y(fm). I listen to them sometimes. They still call us bubblegum musicians, we don’t mind about that. I mean that’s what we created in the 80s, and if it wasn’t (for) us, they wouldn’t be here today. And they must thank Brenda for that. Because if it wasn’t (for) Brenda, I’m telling you, even now, people would still be listening to international music by now. Not even having trust for their own people. Only Ladysmith Black Mambazo and the Soul Brothers would have been surviving by now.

(What was your experience of censorship at the SABC, particularly when trying to mix different languages?)

Back then it was difficult because we didn’t understand why. I remember my album was banned by the SABC. That album was called Shame Boksburg [1989]. You remember in the 80s in Boksburg whereby those guys, these conservative people, they didn’t want black people to stay in those parks there. But those guys were the ones who were cleaning those parks. And my uncle was working there too. And then the SABC didn’t want to play it. And then they sent people to come and break my windows. They were even looking for me at each and every record bar. They were even paying people – they wanted to see, who is this Sox? Then I met them in Johannesburg. They said, ‘Guys, this is Sox.’ And they look at me, and they look at the cover of this album. They said ‘No, this is not the same Sox’ (laughs). Because I look different from the album, different haircut. So they said, ‘No, this is not him.’ I don’t know what they wanted.

But the SABC, then, it was difficult for those DJs then. They didn’t know what to do. I was not even allowed to sing a Zulu song, because I’m a Sotho. And Lesedi FM didn’t play it. They wanted you to play your own music. Either it’s English mixed with Sotho, then it's good. And then, those guys at Natal, if they want to play my song, and its written in Sotho, they can’t even pronounce it, they won’t play it. Because they don’t know what does that mean.

But things have changed now. They’re playing everything.

|

| Come Back Home (1988) |

(Your 1988 debut album Come Back Home - did the SABC play it or was it censored?)

One, this one, ‘Siyafana’ - it was English and Zulu, it was only played on Ukhozi FM. It was called Radio Zulu then.

Those (radio stations) who are playing Sesotho music, and Tswana, they will play it for those (audiences), when I sing English mixed with Sotho. If it’s Zulu, the big radio stations, Ukhozi FM, they will play it. They will choose from the album, they will listen to it first. You know, Radio Zulu have never played ’Le Ja Pere’. Do you know why? Because they didn’t know how to (pronounce) it. Instead, they were playing this song, ‘Come Back Home’, it’s English-only — and ‘Siyafana’, because it’s Zulu.

That’s where that (sleeve) picture comes in. The person who came up with the concept of this cover was an engineer, Simon Higgins. He was the one. He bought me this jacket at Park Station there. This suitcase was carried by someone else, and then he gave that guy R100 so that he must have this thing. It was empty, and that guy was very happy. This photo was taken here in Thembisa. It’s next to the cemetery, but its not like this anymore, because there are RDP houses there now.

Even Chicco, you know, ‘We miss you Manelow’ - Manelow was supposed to be Mandela anyway, but the SABC said, ‘No, we can’t play this tune.’ He said ‘Manelow’ and then it was a different story, they said ‘fine, this is good’. But he knew what he was singing about.

(Didn’t censors realise?)

Some of them did know, but the rhythm of the song was good, so all the DJs were excited about the song. But when you mentioned the name Mandela, then they freaked out! They said, ‘No, we can’t play it! We can’t play this, you have to change this.’ Then Phil Hollis called Chicco and said, ‘Chicco, look, you have to change this Mandela thing to something else’. And Phil Hollis is very creative. He said, ‘Look, why can’t you call this Manelow?’ It was Phil Hollis’s idea.

(What was it like working with Phil Hollis?)

Phil Hollis was good. He’s like a black man in a white skin. Phil Hollis can hear a hit when somebody just brings a demo tape there and he listens to it. You know what he did, with ‘Manelow’? He took that album, he went to a shebeen in Soweto, he bought people beers, these pantsula guys. He said dance for this song and I’ll buy you beers. And those guys, they danced. He said, ‘No, this song must be a bit slow’. He phoned Chicco and said, ‘Chicco, make these pantsulas dance. That means you have to up the tempo. This song, it’s a bit slow. If these pantsula boys can’t dance, then this song is not going anywhere.’ He knew!

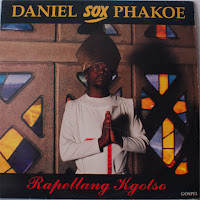

|

| Rapellang Kgotso (1991) |

(Would you say white people played a positive role in the music industry, or not?)

Some did contribute. Some were exploiting people.

(Why do think most engineers back then were white, not black?)

I mean I can’t blame anybody for that. Our black brothers were not exposed to being engineers. Because they thought if you go to school for that it takes a long time. Just like doctors, you know, you go, you qualify after seven years, or something like that. … Some of those white engineers, they did help us a lot in the past. They used to show us how it’s done, like Ian Osrin.

(Was there a lot of exploitation?)

All of them (other labels), they were doing the same thing. Musicians used to come and go out from Gallo to go to EMI, EMI was doing the same thing to others, then others joined the other companies…

(Was it racial exploitation of just part of the business?)

It was business. They’re ripping musicians off. Those black guys, when they became executives, they were worse than those white people!

(Were any white artists popular among black audiences?)

It was only PJ Powers. White people did like PJ Powers, but she was liked the most by black people. Because she used to sing a little bit of Zulu there, even if it was not perfect. Zulus were crazy about her. They even gave her the name Thandeka.

Mango Groove. Juluka … can you imagine the first time I watched Juluka? Seeing Jonathan Clegg on stage. Here in Thembisa. I remember looking at that group playing there. There was a lot of people in the stadium, if only 5 or 6 white people. And when Jonathan Clegg did that dance… he did it more than Sipho Mchunu… and people like him more than (their) own — Sipho Mchunu, the Zulu guy, who had heads of cattle in his hometown and everything. People said that white guy, he can do this better than Sipho! Sipho used to take Jonathan Clegg to Mai-Mai, there in Jeppestown, to go and see those Zulu people dance. And you can even see, when Jonathan Clegg walks, he’s like a white Zulu mamba! (laughs)

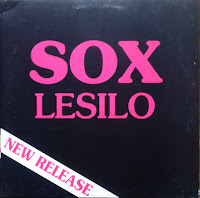

|

| Lesilo (1994) |

They were calling Mike Fuller the police of the music industry. He was the only white guy who can go around all these townships. That time it was only white policemen who were coming. They knew who he was, (but) they portrayed him as that (laughs) - as the police of the music industry. He’s the guy who discovered Rebecca Malope.. I remember the stable was in Bree Street or something. Ali Katt was in their stable - ‘Let the Good Times Roll’. That guy who was singing just like Teddy Pendergrass - he had a beard, they called him Ali Katt. And then Hotline was in their stable. And there was this group called Casino, who was at Mike Fuller Music. And there was Zone 3 that was in the same stable. That was MFM stable.

(Have you toured/performed in other parts of Africa?)

Many times. I know Botswana like the palm of my hands. Lesotho, Swaziland. I’ve been to Kenya, Tanzania. I’ve never been to Zimbabwe and Maputo (Mozambique). Those are the only two countries that I’ve never been to.

(Did journalists ask about apartheid?)

They did, but the promoters sometimes they told us not to speak to those guys. Especially if they (want to) talk about South Africa during the 80s, especially politics. Sometimes I didn’t have to say anything. Because I don’t know, sometimes you find that you are in a hotel, and those guys from Umkhonto we Sizwe, they were there. And they know who I am, and I don’t know them. Some of them, we only find them on stage, operating those lights for us, then they tell us after where they are from.

(Were there difficulties returning to SA afterwards?)

We were scared at first. I remember one time when we crossed the Botswana border post, Tlokweng, (to) come (back) to South Africa. I remember they stripped our Kombi there. I don’t know what they were looking for … maybe (they thought) we were using explosives in Botswana, or whatever the case is …Ei, it took about 3 hours there … they were searching everything. But they didn’t find anything. They just said ‘OK, now you can go.’ (it happened) especially if we come from Botswana, coming to South Africa, at the border post of South Africa.

It was just like in Angola. (Sox performed in Angola too) Ja I did, with Sidney, that guy who was singing ‘Mama’s Baby’. And Johnny Mokhali, who was the Michael Jackson of Botswana … He’s staying in Mafikeng, as I understand, now.

And then we went to Namibia. They said there was a big festival there. We went to Namibia - Ondangwa. When we arrived there, I was surprised because instead of going from OR Tambo (airport in Johannesburg), they said ‘you’re going to take a flight here in Lanseria to Namibia.’ And we were surprised to see the (plane) in camouflage. I said, ‘Why is this flight like we are going to a war zone or something?’ William Mthethwa said to me, ‘You talk to much!’ (laughs).

It was us, Yvonne [Chaka Chaka] and everybody, We went there and when we arrived, only to find that there was elections in Namibia. The first election. I don’t remember the year, but it was the first election of Namibia… and then the festival was organised by this party called Turnhalle (DTA) - it was South African soliders, mixed with some white people from South Africa, wanting to take over from Sam Nujoma, which was SWAPO. We didn’t know anything by then. Only to find out that we are wearing T-shirts, written ‘Vote for Turnhalle’. I said to William, ‘Look at this, are we going to vote there or what? We have never even voted in our own country!’

We did the concert, only to find out on the radio after the election, on the radio on our way to Windhoek, they said ‘Sox and William and Yvonne, they were performing for a party called Turnhalle, in Ondangwa. That means they voted for that party’. We have to go straight to the station and tell them, ‘We were just organised (hired), they said there was a festival but we were surprised, it was just a plain field there. People were not paying anything there, it was just (the) election, which we didn’t know. We have never experienced that before.’ Dang!

Then I remember what happened in the 80s, when there was this song called ‘The Peace Song’ (‘Together we will Build a Brighter Future’, 1986), that was played here in the 80s. Lazarus Kgagudi, Blondie Makhene. Yvonne Chaka Chaka sang on that song, but Phil Hollis said, ‘No, Yvonne didn’t sing’ (to protect her reputation). That song was about peace, but … then AZAPO saw that firsthand. You know how they burnt the houses of those guys. Steve Kekana’s brother was killed, because of that. Blondie had to run away. William Mthethwa was singing there. Suddenly, after, people houses were burning. Nobody wanted to say, ‘I wrote that song’.

It was playing on all these radio stations ... and then AZAPO says, ‘Fuck, this is a shit song. Who is singing here? This song is promoting National Party.’ They said that song was promoting the ruling government. I don’t know … We never had a chance to listen to that song, and suddenly people’s houses were burning. Nobody wanted to hear that song any more.

|

| Don’t Call Me Sejabana (1993) |

You must ask Blondie about that song. Maybe he’s scared to talk about it now. He (had to) seek refuge in Lesotho. And then he had to come back and have a meeting with AZAPO to solve the problem. Blondie had to go to Lesotho, he had to leave the country. I remember when I met him (recently) in Macufe, I asked him about the same song, he said ‘Sox, you know you’ve got a very good memory for a lot of shit things!’ (laughs)

(Did apartheid close SA artists/audiences from other African sounds?)

How long have I know Oliver Mtukudzi? I knew him from 1980, when I joined Hot Soul Singers. They [Hot Soul Singers] were playing this kind of mbaqanga music then, they were competing with Mahlathini … I was just a member of the band, a backing singer for the Hot Soul Singers. Then we went to Zimbabwe, it was Independence Day. Bob Marley was playing there. (I was there) with Hot Soul Singers. I was not even… nobody knew who Sox was then. I remember seeing Thomas Mapfumo, who was a hit in Zimbabwe then. Devera Ngwena. And then Oliver Mtukudzi. Bob Marley, for the first time. Imagine – it was like I was dreaming or something.

And for the first time, seeing Robert Mugabe, being sworn in there in Salisbury Stadium, Harare. Dang! I was just from school, in the Free State. Coming here in Thembisa, and then the next thing, I’m in Zimbabwe, seeing all those things. Bob Marley – I never thought I would see that man. Robert Mugabe, Kenneth Kaunda. All those people we were taught about at school, seeing them there. Dang!

I listened to Thomas Mapfumo, he was a superstar there. But when Oliver Mtukudzi, the youth of Zimbabwe there, they knew, this man is going to be big one day … And now he’s staying here [in SA]! Somewhere in Midrand.

(Back then, could one hear Tuku in SA, eg on the radio?)

No, no, no – we knew American stuff. South Africans always liked American music.

(Here in SA, when did you get a sense things were changing politically?)

After Mandela was released [1990], the music industry changed. Then it affects us, from the bubblegum music. every DJ didn’t want to play that kind of music anymore. They wanted to play the genre music of kwaito. And more international, house music, hip-hop. Even if you want to make an album now, you’re asking yourself, are they going to play it there (radio) or not? There was this kind of quota and all these things. All the radio stations started to listen to the music and (ask) ‘is it fit to play it on this radio station, is it fit or not?’ making people to phone in – ‘is it a miss, or is it on?’, those kinds of things. You can imagine how embarrassing it is for some people to be in the studio there, people telling you your song doesn’t fit to play in that station. It was the end of it.

The changes came in the ‘90s, when people like Spokes H comes along. And then these kwaito guys come along. Then everything changes… Kwaito music has changed the complexion of the music industry completely …

The guys, these kwaito boys. They have their publishing, everything. That’s how they’re making money. Even if they go to SAMRO, SAMRO gives them 100%. But I have to share that 100% with Eric Frisch. I get 50 from SAMRO, the other they give it to Eric Frisch.

|

| Codesa Jive (1992) |

My music is only played on one radio station – Thobela FM. All the other radio stations don’t even bother to play our music. It’s only that station that plays. Now. Even our brothers in the SABC, here at Lesedi FM … they don’t even bother to have a programme that can play oldskool music. That’s why the record companies have realized this now, that’s why they’re making The Best of Sox, The Best of Chicco. These guys from the taxis, they miss that kind of music of the past. It’s 20 years later and now it’s back in business.

Bubblegum (also) ended when Brenda died [in 2004], anyway. She was the only one who was sticking to that kind of music. She was the one who started that kind of music … Brenda from ‘83, she was ruling the music industry, until she died.

(Are sales low these days because of piracy?)

They use that as an excuse. They talk about piracy. They (record companies) are the ones who are pirating music too! That’s what they do!

(What are you up to these days?)

Right now, after February [2010], I’m going to (work) with Dan Tshanda of Splash. All of us we started in the 80s, as bubblegum musicians. We still tour Botswana and Namibia and whatever. I’m doing to do an album with him. He read about my story and he wanted me to come back to the music industry. He said ‘look, people in Botswana, they still want to know what happened to you. You still have a name, as (far as) we know. so we can make an album there, and you promote it’. Together we are going to mix Venda and Sotho music together… I think it’ll take us maybe 2 to 3 months. Because he wants to use some live instrumentation. And then he said I must bring along the guy who was producing my songs, the second assistant producer, Malcolm X. So I’m going to bring him along. Then we’ll mix that old stuff with Dan. It’ll be a different sound, but … I wait for them to make the music, then I write (lyrics). Even if they can make one song there that can make me sing the very same day, I will do it.

© Afrosynth

May his soul Rest in peace his music will be forever missed.

ReplyDeleteRezt on peace Sox you are alegend

DeleteAMEN!

DeleteGreat interview, Sox was an interesting character and had an eventful career, even met Bob??

ReplyDeleteThanks Okapi!

We miss sox for sure

ReplyDeleteI even play his music right now anyway rip boel

ReplyDeleteJo Sox mr le ja pere he was an icon le his soul rest in peace

ReplyDeleteRest in peace Sox

ReplyDeleteRest in peace Kakapa "listening to where did she go from album mama"

ReplyDeletethis is the music l lived through and loved, thank you Sox, RIP

ReplyDeleteRest in peace the legend

ReplyDelete