|

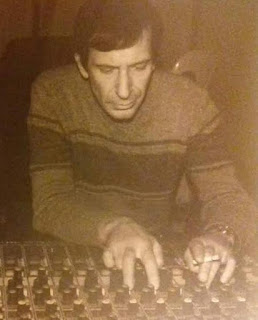

| John Galanakis |

John Galanakis was a hugely influential South African label head, producer (of the soon-to-be reissued Starlight with the late Emil Zoghby, among many others) and musician. The following is a transcription of an interview with him at his home studio in Greenside, Johannesburg, in December 2009. Galanakis passed away in August 2018 (four years after Zoghby, RIP). This interview has been edited for clarity.

(How and when did you get started in music?)

Late 60s. I played piano, keyboards. I first started doing sort of ‘continental’ music in nightclubs, and things like that — Latin, Italian, Spanish, I played in a Greek band. It used to be a big thing, especially (in) nightclubs — start at 9 and finish at 4 in the morning, and on weekends at like 6 in the morning. We used to get tips. I used to play the bouzouki. Your tips ended up being much more than your salary. A lot of these guys came from out of town, café owners or … and they’d never been exposed to the Greek culture, so they went mad when (we played).

I got into rock bands, jazz bands as a keyboard player. And I’d say in the 70s, I started doing studio work as well. I was completely self-taught. I never took piano lessons or anything like that. I had an ear, from a youngster. I was sort of at a disadvantage because I never bothered to kind of get down to reading and studying. Later on, when I started doing studio work, I had to do that. Then of course, some of these gigs, I did some cabaret, so every week we used to have a different cabaret artist who’d come with a pile of music, so you’d (only) have a couple of rehearsals and you’d have to (be able to) play his stuff.

Late ‘70s, I played in some very good rock fusion and jazz bands. DICKORY was probably the main one. And ‘78 I went to London for 3 years, to get into the music scene, and production, which I started doing, and arranging.

(Why — to be in a bigger pond or to leave South Africa?)

Both. Well, TREVOR RABIN was there at the time, and (we) got into a band together, we formed a band. With the bass player who was with us in DICKORY, LES GOODE (later an) engineer, and a great bass player, and businessman. We toured Britain and that tour actually got him a deal to go to America. And he left us behind! I think we were a bit too old, ‘cos his image was more teeny-bopper. And we were like 30 at the time, (which was) much too old (for that). This was ‘79. Sort of pop-rock — a very good band, I must say. Just (touring) the UK (not Europe), we didn’t record. He’d sort of recorded an album on his own, which he played live. We got it down exactly the same as the record.

And then I was also doing some productions with EMIL ZOGHBY – lots of stuff, from porn sci-fi movies [probably alluding to 1979’s Spaced Out, aka Outer Touch], to (the) brother of NAT KING COLE, FREDDY COLE – we did an album for him, sort of big band style, orchestral, and all that kind of thing [1980’s Right from the Heart, where he is credited as John Gally]. He (Zoghby) was mainly producing, I was the engineer, arranger, and musical director. (I) wrote out all the parts, and things like that.

And in 1980, we got a call from that same bass player, Les, to come back, because they were starting this ‘supergroup’ – MOROCKO, based in Joburg. But there was some management with money, that wanted to take us to the States and record, which we did. And we came back (to SA) and we rehearsed for about 3 months. We went to California – just outside San Francisco, Modesto, and we recorded an album there. The management were so - not together – it was an American and a Canadian, and they employed a South African manager to sort of coordinate the stuff. (But) they were more into the jol [party] that the actual (music). This was actually a very good album, although we had to remix it when we came back here, because the studio wasn’t equipped for mixing, basically. The band only lasted about another 6 months or so, here. There was always the chance that we were going to go (back) to the States and do a tour there, but I don’t know, egos got in the way, or something.

(What was it like to be an SA muso in the States then? How were you received?)

Well, we didn’t really … we were in the studio the whole time, we never really did tours or anything like that. The people who were involved were thrilled to have some people from Africa — “How can they play like this?!”, you know, ‘cos we sounded just like an American band. Which was probably the downfall of the band, it wasn’t too different enough from the mainstream American sound at the time. Although for South Africa it was like exceptional, because there was nothing like that happening here.

And after that, I got a bit fed up with musicians and egos and that, and I just got into the studio, producing and arranging. And EMIL ZOGHBY came back here (to SA). We worked together for about 3 or 4 years, doing production … STIMELA was one of the groups .., (working with) not so many black (artists), a lot of white artists. MARA LOUW was another one we recorded.

And then ’85, I started my own record company, with a guy called BLONDIE MAKHENE — Hit City. And we had three labels: one was Leopard Records which did our traditional stuff – it was black music. We had the White Dove label, which was mainly the gospel stuff, and then the Hit City label was the pop stuff, the disco stuff and that kind of thing. Even there (Hit City) there were very few white artists involved in the thing. A couple of ‘coloured’ [mixed race] groups – called ZIPP, which was phenomenal, but they got nowhere. I think in Cape Town it’s (the coloured music scene) bigger. In the old days I worked with guys like RONNIE JOYCE and the guitarist JONATHAN BUTLER. And there was another guy, LIONEL PETERSON. (I working as an) arranger/producer, not so much (in) the songwriting with those guys — the arrangements, and getting the musicians, and rehearsing them, and recording, helping with the production in the studio.

(Was it a healthy time in the music industry, with the emerging ‘bubblegum’ scene?)

Yes, I think so. It was kind of slated later, in fact it caused our demise in the early ‘90s, because the DJs just decided we’re not gonna play any more bubblegum music, and they switched completely to playing overseas house and rap music, so they actually dropped us in the lurch. The actually built us up originally. But our most successful stuff was the traditional and gospel stuff. This group PURE GOLD went on to sell a couple hundred thousand albums. (and) they did get a name overseas. It’s faded now, but they were a big name in the gospel department. And on the traditional side as well, we had guys like DAN NKOSI, ZIZI KONGO, things like the AFRICAN YOUTH BAND.

(What did you make of the ‘bubblegum’ label?)

I think it was like the dance music of the time. We used to call it disco at the time — it wasn’t really American disco, it was South African disco … dance music – bass drum type … predecessor of kwaito, basically. I think later, people started calling it bubblegum (in a derogatory sense), especially the radio DJs and that kind of thing. And a lot of the records were starting to sound the same, copying the same style and the same beat, and the same rhythm, and the three-chord sequence that everybody was using.

I think it was thriving from about ‘86, ‘87, it started fading I think around ‘92. I think it still had legs to go, I mean with a style like kwaito – how long has kwaito lasted? It’s still there, they’re still making kwaito records, 20 years later. But they killed it, basically, they stopped playing it completely on radio.

(Was this related to political change at the time?)

I think so. There was a lot of American influence in that kind of music, together with local sounds and rhythms, but American production techniques and instrumentation – synthesizers of course, which have such a bad name.

(Was there competition/rivalry between producers?)

No, it was more (about making) slight changes to what was established, basically, and getting the synth to sound just as close to acoustic instruments as you could, or making it so outlandish that you could hear that it was a synth — so from the one extreme to the other.

(Was there a strong American influence on SA music then, or more African?)

The pop stuff, the sort of black American rhythm and blues type music. (African influence was) mainly on the rhythm side of things, maybe the drum beats and the percussion and the basslines, and that kinda thing. And the guitar riffs – melodic-type African guitar riffs and rhythms and things like that. (We were) mixing a little bit of traditional into like rhythm and blues and pop.

And also at the time – it’s changed a lot now – there was a tendency to make black music with English lyrics, maybe have a catch phrase with an African saying – or something that’s happening in the townships, (but mostly English). I don’t know (why), I think it was just a fad. Of course the American records were so popular at the time, (people thought) ‘let’s combine American style with African rhythms and see’. Like BRENDA FASSIE and that kind of thing, which was a whole style on its own. Can you believe somebody like ZIZI KONGO was competing with BRENDA FASSIE, didn’t make a tenth of the money, but she’s still around. And we also did some albums with BLONDIE as well.

(What labels did you work with?)

EMI was distributing our stuff (but) it was our own label. (EMI handled) distribution to the shops and things like that. We were still responsible for all the marketing and production. (ZIZI KONGO and others) they were on the Leopard label. ‘Cos even though a lot of their songs were in English, they had a more traditional feel to them, a heavier African rhythm.

(Was there competition between different labels/stables?)

Ja very much so, it was very competitive. We were across the road from Gallo, we’d try and spit at them (laughs) because they were big and powerful and (would try to poach their artists) absolutely, and sort of stop you from getting publicity, and giving deals to dealers that you couldn’t actually match, and things like that. And of course, it still is (like that) ... We were always independent.

(How did labels and musicians make money?)

Record sales were probably the only way to make money (for the label). There were shows that the artists, once they got big enough, they could command quite high salary, high fees, but we never took anything from their live performances. They did their own – although we helped promote their shows and things like that.

(What about live shows, festivals in townships etc?)

We put on a couple of shows (but) it wasn’t our main thing. And mainly out of town, in places like Swaziland, and Lydenburg and…quite a few tours we did of smaller towns and halls and things like that, a couple of festivals in Swaziland and Lesotho, and in the Cape, near King William’s Town.

(What was it like as a white guy involved in predominantly black music back then?)

People were very welcoming. I used to go into Soweto and do promotions on a regular basis, maybe twice a week, go to shebeens and pubs and that kind of thing. It was calm. But it started getting a bit hot towards the end of the 80s. They told me ‘don’t go there anymore’, the black guys said that, ‘it’s not safe to go there’. So I stopped going. At these festivals, I was the only white face, sometimes, amongst 20,000 black people. It was cool, and they were actually excited to see a white face. Some of them had never seen a white face, in that kind of setting. They’d always wanna talk to me and shake my hand and that kinda thing. It was really cool.

(Were there crossover acts, eg. black artists who sold to white audience?)

There was hardly any of that, that I was involved with anyway. The tastes were completely different. White people didn’t really seem to like the black music, or the traditional, or the gospel stuff. So there was like a chasm between the two kinds of music. The closest we got to bridging that was the [group ZIPP that we recorded. It was basically a rhythm and blues, popish, with a slight African influence in it. The main guy, Ziggy (Adolph), he’s up here now — no, they’re from here, from East Rand, but I think Ziggy was born in Cape Town, and I think Paul (Green), the singer, was originally from Cape Town. But they’d been here for most of their lives.

(Did labels have deliberate racial target markets?)

Ja, and very little (crossover). Sometimes you hoped it would cross over, but white radio stations would never play that kind of stuff. So there was never a chance for whites to even hear it, and appreciate it.

(Was this official government policy via the SABC?)

Ja I think they wanted to keep it separate. In fact we used to have to be so careful with our lyrics, ‘cos (the lyrics of) every record had to be submitted to the radio station. On one occasion, they were convinced one of our artists was actually singing completely different lyrics to what we’d given him and they said they were trying to pull the wool over their eyes, but they were actually hearing things. They were imagining that they were hearing something that wasn’t there! We had to actually change the lyrics. We had to re-record the record, after it was released and everything, they wouldn’t play it. You’d give them a released (printed) record (not the masters before release). They wanted a record.

(Then there was) Self-censorship – you’d censor it yourself. You’d be so careful. And this goes back to when I first started. Radio 5 and those guys used to only played a certain formula that was acceptable to the format of the station, and nothing that even smelled of political or anti-government (sentiment). (There was self-censorship) because you know they’re gonna ban it if they hear anything that they don’t agree with. And it was very difficult, even in the white market, before I started the black label, to get anything played locally, because they had about a 10% quota for local stuff. Everything else was American or British. And that 10% had to be exactly like the American stuff, to fit to their format. It couldn’t jar or be too different.

(Who was pushing the envelope? Was this pop or political music?)

Well, I had a group of my own. Well, it was a studio group, we never really toured or anything, called BANJO. And we did a quite a few records where the lyrics were on the verge – they had a double meaning, a lot of them. One was called ‘No No No, No More’, which was supposed to be a fight between a man and a woman, but it was actually trying to say to the government, no more. It actually made it past the censors. So you had to be subtle. It was possible to do, in a subtle way, but whether the crowd got it, you don’t know.

(So you’d say the industry was healthier in the '80s compared to now [2009]?)

I think so. I think it was probably in its heyday in the '80s … and (in terms of) establishing artists. I mean there were a handful of black artists (before the 80s) that were household names among the black population, but I think in the 80s that blossomed out and you got hundreds of artists that became household names … But it wasn’t just automatic, it had to have something that the market wanted, like catchy or memorable.

(Why the change — was it politics, technology, international trends?)

I think it became … I don’t know. Politically, I think, after the ‘90s, it became a lot easier to have a black and white band, for instance. Before that, it was almost impossible. And (it was easier) for blacks to start appearing at white venues, and the other way round. You started getting blacks appreciated jazz, and even rock, and putting those kind of influences into their music.

(Wouldn’t that make things better though? Or the opposite?)

Well I think a lot of things happened at the time. I don’t know if they were political or not. But it probably changed people’s perception of what was…. and I think the (radio) DJs played a big part in that kind of thing. They actually changed what people were listening to. Radio DJs started really promoting American rap and R&B, and things like that, (in the) early ‘90s.

(Where did kwaito come from?)

I think bubblegum influenced kwaito, and also the American rap influenced it quite heavily, because its based on that rap.

It’s still big today, but bribery (payola) was actually the big thing that influenced the DJs and the record companies ... and the big record companies could bribe the DJs much more than the small record companies, the independents. So they obviously got more favour. And they were flown from Durban to Joburg for soccer matches (for example). It still happens today. And some of the notorious ones used to actually pay them something to play their record, and pay them something extra not to pay your record.

(How was it working with French singer Lizzy Mercier Descloux on her 1984 album Zulu Rock?)

Not so good memories. Cos I did my best there. She was a complete — worse than a snob. But I don’t know if this record was successful. I did all the arrangements and the musical direction. And in the end I didn’t get paid for it. That was the management. I hardly had anything to do with her. She hardly said five words to me. Even though I was in the studio every day with her, she almost ignored me. She liked the black guys, I think that’s what she came here for! (laughs) but that management was really — they didn’t know what they were doing. She was quite good, quite good, but I think we had as good singers that are performers here in South Africa. She wasn’t exceptional.

It was quite interesting for me too, because it was like a gelling of local and European influences, and the music sort of had an African feel, but with European singing, and chords, and things like that. And the final product, I don’t know if it was that exciting for me, as well. I think the idea was more exciting that the actual finished product.

Not that they weren’t musical or anything like that, they just had fixed ideas of what should happen. They basically wanted to use the African for the rhythm, and then their polish, or something, on top of that. But they weren’t musicians at all themselves, they were more managers, business guys. And they seemed to know what the market would take in France, or Europe, or wherever it was they were look to sell it. Well, I can understand… I don’t think what happens locally can make it overseas as it is. It needs – not polish as much as sounds that they’re used to, and melodies that they’re used to, something that they’re familiar with and they can understand. I think the rhythm part, which is African, is exciting for them. But if you had to put African lyrics, it would throw them completely, far away.

(Did this project have political intentions or was it purely commercial?)

I didn’t understand the lyrics, because they were all in French, but I don’t think it was supposed to be political or anything like that. It was just supposed to be pop — and actually the French have got a very big scene going now, with African music, mainly from northern African countries. And I supposed it started there, and they were trying to do something with the South African sound, trying to incorporate it.

I never heard anything. They promised to send me an album when it was finished, but they didn’t even send me anything. I think the musicians got a session fee, normal for three-hour sessions, but they didn’t give me royalties or anything. I didn’t get any royalties.

(Did you sign a contract?)

No, I’m very bad with that kind of thing. I take people on their word.

(Were any black SA acts making waves overseas?)

Gee, I don’t think I know of any black artists who were actually making it (overseas).

(What about elsewhere in Africa?)

There was very little of that (too), up till the late ‘90s, mid-‘90s.

(Was SA scene very isolated?)

Ja it was, very closed. The South African, African sound. Even though a very of our groups did perform in Zimbabwe, even in Kenya. Like PURE GOLD actually did some very good tours…

(And in Europe?)

I think they did one or two shows there, but nothing you’d call a tour … We tried to get them released, but their music was so different to what was going on, on the scene.

I think in a way the PAUL SIMON idea was the right one, and even this French (Descloux’s) idea – take something from it (here), but not completely, not like a whole package. Take what’s palatable for them, and mix it with their kind of style. PAUL SIMON sounded different enough for it to become a big hit. (but) It was still a pop record.

Even JOHNNY CLEGG had the right idea. I’m not particularly a fan of folk-type music, which was his bag at the moment. That’s what he mixed with African influences. But still, that kind of idea could’ve worked if it was like developed properly. And it can still work, take the best of African rhythms and melodies and things like that, and mix them with pop.

(In SA, was there cooperation between black and white?)

In the studio, yes. A lot of black producers used to work with white engineers.

(No black engineers?)

There weren’t.

(Why not?)

I dunno, they were never trained, they were never given opportunities, I think. As producer, they actually made their mark. And I think from there, they went into engineering.

(Any other stories, perhaps about repression back in the day?)

Repression ... for instance, we had this group called the VENDA KIDS, youngsters, about 15 to 18. And they came from Venda. Mainly a traditional style of music, but also in a kind of disco/kwaito type of beat. And it was the time of the troubles — ’88, somewhere there. After a recording session they were gonna catch a taxi and go home. And as they were going to the taxi, police raided them and started beating them up, in the taxi. And I had to come and explain, ‘No, they’re not terrorists or anything like that, they’re kids!”

They (the musicians) weren’t supposed to (be out) — it was quite late at night, 9 o’clock, after we’d finished recording, and I think there was a curfew or whatever, and you weren’t supposed to be walking around the centre of town at that time. And I had to go and explain to the cops: ‘These guys are musicians and they’re just going home’. (the cops were) ‘OK, fine,’ after I talked to them. But they were really heavy, beating them up with batons and things like that.

Another time, we did a tour, and we went to the Free State. Coming back, we were stopped at a roadblock. There were blacks and me in the car. And of course, that’s very suspicious, you know (laughs). PURE GOLD were there, and BLONDIE was there. And they made us get out the car. The blacks had to lie face down on the ground, while I opened the boot, (with) two guys pointing guns at me, in case I had a machine gun or something in the boot. We had a few records and cassettes, and clothes and things. Every time I took something out, they were watching me and pointing the gun at me … after they saw that we didn’t have (anything dangerous), then it was fine, they’d let us go.

Another time, we had a tour, we went through the Transkei. Those days if you went from Durban to East London, which we did, you had a border post going into the Transkei, and border post going out of the Transkei into South Africa, for about 10km, and then another border post going into Ciskei, and then another border post going out of Ciskei into South Africa. (Cops were) all over the place, so you had to produce your passport. Now we’d discover, as we’re going to the Transkei, half the guys didn’t bring their passports, and they wouldn’t let us through. So what we did, we performed for the border guards. We gave them a whole show for about half an hour, and they said, ‘just go through!’

The funny thing to see is at Durban airport, it used to say ‘International flights: Umtata' [now Mthatha]. Local flights, Joburg this way, and ‘international flights’, that way!

(So it was possible to relate to cops sometimes?)

Ja, they were doing their job. They were hardegat [hard-ass], but with a bit of a smile and a song, you get (through) — (like) bribery and corruption, same thing as today! So we did about 4 performances to get through. We were in two minibuses, so we had the whole of PURE GOLD, which is like 11 people, in the one and a couple of other acts in the other bus.

(Was police intimidation a common occurrence on the road?)

Ja, it was part of the (deal). The stories I used to hear from the musicians themselves … DAN NKOSI used to stay in Ermelo, which is a real centre of conservatism. And he used to go and visit a coloured musician and spend a few hours with him, practising and playing and doing some songs. And then because it wasn’t (in) a black area, he would have to walk – it wasn’t far, but he would have to walk through his area. And it was like, after 8 o’clock at night, they’d catch him and beat him up. So he became quite blasé and used to it. He’d say, ‘Ah, it’s late, so I’m going to get beat up again tonight!”

(What was it like for you to go into Soweto back then, for example?)

You were supposed to apply for permission, but I never did. And I never got stopped. Maybe I was just lucky. I heard other guys got stopped. And very few whites actually used to go there. Some engineers used to get permits and permission, because there were no black engineers. So if you were doing a show in Soweto, you’d have to get white engineers, that kinda thing. The big record companies used to have black promoters and managers who used to travel with the groups into townships, so they didn’t have problems.

(Did you ever live overseas?)

No.

(Weren’t you ever tempted to move overseas?)

Ja I was tempted, many a time, even before as a pure musician. And a couple of my friends actually went there. I got married quite young, so I had a family and everything, I couldn’t just up and go. It was also very difficult to get in, those days. Especially without money. So I could just go and work there, and try and make ... although, in hindsight, it’s what I should’ve done.

(Was it a choice between making money overseas or pursuing your love for SA music?)

Well, I like money too! And we were successful for about three or four years. Everything went down after then. And even now, I’m battling.

(Who are you working with now [2009]?)

Mainly I’m doing black music, I’m still involved with a couple of guys. One guy, MBUSO KHOZA, he produced some gospel stuff with me. I’ve got CDs in the house… I did an album for a religious group called the Shembes, it’s actually the second-biggest church in South Africa, based in Natal, sort of old-testament type church, very traditional. We had a couple of singers, but he recorded all the harmonies himself, quadruple tracks, every harmony.

(Where have you been based over the years?)

In the '80s we were in town (Johannesburg CBD), in Pritchard Street, just behind Gallo. Then about ‘98, I went to Greenside, in the shopping centre. And then we decided to bring it here (home), because we were mugged over there and they raised the price, the rental – they doubled the rent and halved our space! So it’s small, but it’s (got) a very good sound. And I can come to work in my pyjamas!

© 2023 Afrosynth

No comments:

Post a Comment